Why ‘Types’ of Coaching Misses the Point

Why ‘Types’ of Coaching Misses the Point

Recently, I have noticed a debate around ‘types’ of coaching being done in schools. Most of this is in the context of Instructional Coaching and the terms facilitative, dialogic and facilitative are being used to describe types of coaching that are clearly distinct from each other. An unhelpful consequence of this is that it can lead to schools picking a ‘type’ of coaching that they think is needed. I’ve read statements like “we do directive coaching”, for example, and some approaches described as Instructional Coaching appear to be heavily weighted towards the judgement of the coach (as expert diagnostician and prescriber). These look more like feedback models or direct instruction for teachers than what would conventionally be considered coaching. This approach raises issues of power and status and calls us to examine the beliefs that such approaches might be grounded in. Who decides which ‘type’ is needed for each teacher? Helping professional adults get even better at doing what they do requires a deep understanding of human motivation, identity, change and complexity.

Coaching? Instructional Coaching? Mentoring?

The ‘types’ question is not new - now we just have more nuanced labels to apply. Probably the most common question we are asked when working with educators is “what is the difference between coaching and mentoring?” Answers to this question may cite the length or formality of the relationship, typical coaching or mentoring topics and goals, e.g. career transition, and expectations on either side of the relationship. There are always commonalities and differences depending on the source or experience cited. In short, the answer (in education contexts at least) is not as clear as we might expect. A key point of difference that does tend to be clear is the place of the expertise, knowledge, and perspective in the relationship. This is often a key distinction between mentoring and coaching. On the other hand, “ask don’t tell” is a common mantra associated with being a coach. The typical representation of coaching and mentoring on a continuum running from non-directive to directive respectively can suggest a false dichotomy between the two (see Munro, 2020). Then we have the question “so what’s Instructional Coaching?” closely followed by “it sounds a lot like mentoring.”

According to Jim Knight (2018, p12), instructional coaches balance advocacy with inquiry. This means they can offer expertise, knowledge and perspective and temper this with sufficient inquiry to ensure that the teacher is positioned as a genuine thinking partner.

As Instructional Coaching has become more prevalent in contexts beyond North America, the first clarification required has often been that the word ‘instruction’ signifies the topic of the conversation and not the mode of discourse.

A more holistic view

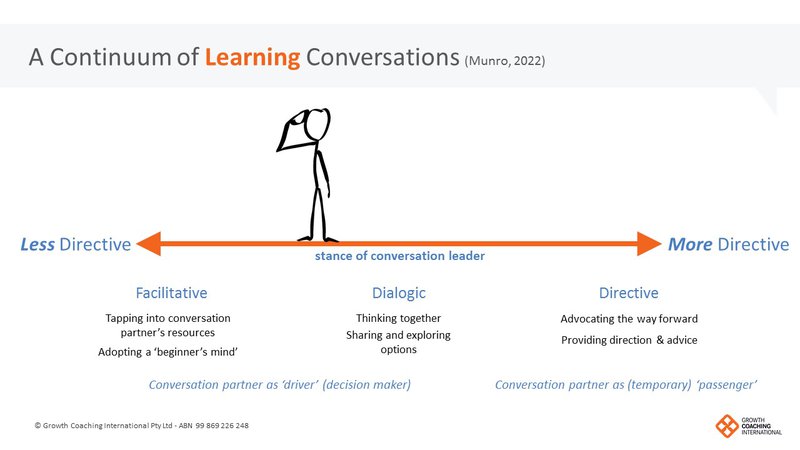

In A Continuum of Professional Learning Conversations: Coaching, Mentoring and Everything in Between (Munro, 2020), I proposed a more nuanced view of how we lead ‘professional learning conversations. This view was about the need to adopt a range of stances as a coach or mentor rather than be constrained by role titles. The ‘continuum’ concept has continued to evolve as shown below. This iteration uses the terms ‘conversation leader’ and ‘conversation partner’ to indicate that what matters is not whether you are ‘doing’ coaching or mentoring, but that you are effectively leading the conversation from your partner’s point of need. This means that the conversation continuum concept can be applied to any leader of learning conversations (see Munro, 2022, for further elaboration).

Pause for thought

- How do you describe coaching, mentoring and everything in between?

- What is the purpose of coaching and mentoring in your context?

- What is your default position on the continuum?

- What dictates this?

- Where would you like to spend more time?

Stance as a leader of learning conversations

Dictionary definitions of the word ‘stance’ offer two meanings, both of which can be applied to conversations. The first, a way of standing or our posture or pose, could mean how we literally position ourselves during the conversation. In relation to the concept of shifting stance along the continuum, we interpret the word more figuratively. This is about how we position ourselves in terms of our contribution as the conversation unfolds – does it need more of me or less of me right now? This may be influenced by the second meaning of the word: stance as an intellectual or emotional attitude. Stance when leading learning conversations is a combination of how we consciously ‘show-up’ and what we do, to best service the thinking and progress of our conversation partner. Shifts in stance are based on high levels of emotional intelligence and finely tuned noticing.

Three indicative stances (not ‘types’) along a continuum

- Facilitative – a less-directive inquiry-based stance designed to tap into our partner’s resources. This requires us to adopt a ‘beginner’s mind’. This means consciously setting aside (not deny) our own knowledge, expertise and experience so that we can focus on supporting our partner to explore their own ideas and the resources around them. This does not mean withholding information that would clearly be helpful.

- Dialogic – a process of thinking together that requires us to carefully manage our contribution as we think with our partner. Here we must maintain an open-minded curiosity that empowers our partner to find their own way, whilst also respectfully sharing some of our own knowledge or perspective in support of our partner’s thinking. Hear the coach is adding some informed suggestions to the ‘pool of options’ and inviting dialogue about them.

- Directive – where more of our knowledge or perspective is required to help our partner make progress. This may involve giving specific advice (more definitive that sharing options), advocating a particular way forward or even some form of direct instruction or training. We are supporting our partner by actively sharing our experience, expertise or insights. Being directive in a learning conversation like a coaching conversation does not mean giving directives.

Facilitative and dialogic stances consciously keep our partner in the ‘driving seat’. That is, they are positioned as the key decision maker in the conversation and should be the ones doing most of the thinking. When we shift towards the directive stance, we are inviting our partner to temporarily move out of the driving seat and sit alongside us as we take control, for a time.

Directedness, Knowledge and Expertise

‘Directedness’ in Instructional Coaching (and Mentoring) is sometimes misunderstood and much of the debate seems to be driven by the assumption that the knowledge of the coach is paramount and that it is about telling or not telling. Telling, giving advice, sharing, and offering, are very different terms and skilled coaches see the nuance and loading in this language.

Similarly, adopting a facilitative stance does not mean withholding, denying or being disingenuous, it means ‘setting aside’. This is a way of managing our tendencies towards ‘helpful advice giving’ (Schein, 2011) and is grounded in an appreciation of the consequences of doing this too soon and too readily. Here, ‘adopting a beginners mind’ is a useful term from the Solutions Focus coaching world. It is as much an attitude as a skill and indicates an openness to learning on the part of the coach and a privileging of the teacher’s voice and thinking.

There are an increasing number of texts and platforms that have attempted to distil ‘high impact practices’ into user friendly formats. These can be helpful points of reference between Instructional Coaches and teachers to help determine options for progress. In the wrong hands, or with insufficient understanding, they can become lock-step compliance or fidelity tools that do not account for the complexity of a teacher’s classroom and their intrinsic motivation. Adopting a facilitative stance does not deny or devalue this knowledge-base. Sometimes perceptions of less-directive coaching are akin to ‘pick your own adventure’ or even the ‘blind leading the blind’. This is clearly not appropriate in an educational environment. When we shift to a less directive stance, we elevate teacher voice and honour their contextual knowledge and expertise. We also treat them as thinking professionals. Far from lowering the bar, done well, we place responsibility for thinking and progress with the coachee.

In short, being a highly effective Instructional Coach requires pedagogical knowledge and expertise but this is notsufficient. Overplaying this component can downplay the need for deep understanding of the human factors involved in working with professional educators.

The ‘what’ of coaching is only one part of the equation. The ’why’ and the ‘how’ are equally important. Teachers at all stages of their development require the full continuum of support from their coaches. Discernment is key.

References

Knight, J. (2018). The Impact Cycle: What instructional coaches should do to foster powerful improvements in teaching. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Munro, C. (2020). A Continuum of Professional Learning Conversations: Coaching, Mentoring and Everything in Between. CollectivED [11] pp.37-42. Carnegie School of Education, Leeds Beckett University. Online.

Munro, C. (2022). Engaging in Professional Conversations. Paper prepared for the School Leadership Institute, NSW Department of Education, Sydney, Australia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372490876_Engaging_in_Professional_Conversations

Schein, E. H. (2011). Helping: How to offer, give, and receive help. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.